There’s a moment in every guqin player’s path when the desire to begin takes form. It rarely announces itself with fanfare. Often, it arrives on a quiet afternoon—perhaps after hearing a single phrase of music that leaves a trace on the air—or when the noise of the world becomes too much, and one begins searching for something that doesn’t compete for attention, but rather, waits.

Then comes the question: What kind of guqin should I buy? And just beneath that, something more primal: Will this become part of my life? Or will it be another object I briefly carry, then forget?

The first step, surprisingly, is not to look at the instruments—but to ask whether someone can guide you. In the world of guqin, knowledge is not standardized, nor is quality easy to judge. A true teacher—someone who protects your path as much as they correct your posture—is the single most important resource when choosing your first instrument.

Why? Because as a beginner, you simply do not have the means to judge tone, craftsmanship, or structural quality. What you hear will mostly be unfamiliar. What you feel in your fingers will lack reference. In such conditions, even the most well-meaning intuition can mislead. And this is why, if you must choose alone, the challenge becomes far greater.

I’ve been there.

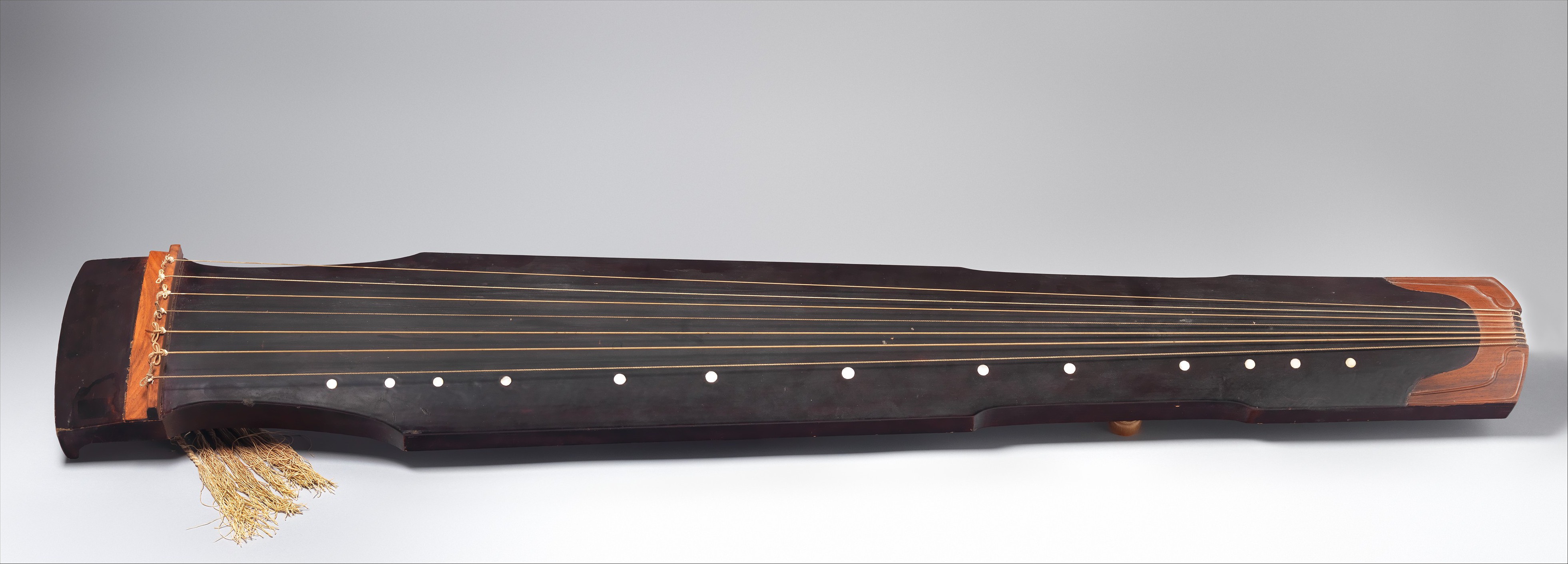

When I chose my first guqin, I had already spent a month borrowing one from my teacher. I didn’t understand soundboards, finishes, or tonal registers. But I did have the luxury of someone watching me play, someone who said, “Yes, this one will serve you.” The instrument I chose—a Zhengheshi made by Xiang Yang—was elegant, solid, and responsive. It was not the cheapest, and certainly not the most expensive. But it stayed. I played it for eight years. I still play it today.

A Guqin made by Xiangyang

Don’t Buy Cheap to Test Your Will

Many beginners imagine they should “start small.” Buy something cheap, just in case they give up later. But this logic is flawed.

A poor-quality guqin does more than sound bad—it actively prevents correct learning. The strings don’t respond, the resonance is shallow, the tactile feedback is misleading. You begin to wonder whether your fingers are wrong, when in truth, the fault is the instrument’s.

What’s worse, these instruments cannot be resold. They have no value. If you give up, they become waste. If you improve, they become a burden. Either way, you’ve lost more than money—you’ve lost time.

So I made myself a promise early on: If I am going to start, I must begin with something that has the capacity to grow with me. It need not be perfect. But it must be real.

What Counts as a Good First Guqin?

Here is the most important truth: the appearance of a guqin tells you almost nothing. Most instruments follow traditional forms. They may differ slightly in shape or polish, but for the beginner’s eye, these are nearly indistinguishable. One cannot look at a guqin and judge whether it is good.

The only reliable marker is this: Who made it?

In the guqin world, there are no trusted brands. We don’t judge by company name or marketing. We recognize makers—real people whose names are known within the community, because they have built their reputations over time. If a guqin was made personally by such a craftsperson—a known and respected luthier—then that alone gives you a baseline of confidence.

If you cannot trace clearly who made the instrument, then price, appearance, and even sound samples are all unreliable.

This is why, for those without a teacher, I recommend beginning your search with reputable makers whose names carry personal accountability. If possible, speak to them directly. Ask how they built the instrument. Ask whether they tuned it themselves. Often, they will answer. That conversation may be more important than anything else you could read.

Don’t Buy Something Too Expensive Either

Unless you are also a collector or connoisseur, buying an elite-level instrument as your first guqin can be equally problematic. Not because it won’t serve you well—it might. But because it changes the emotional posture with which you approach the music.

When an object is too precious, it begins to intimidate. You worry about every fingerprint, every accidental tap. You hesitate to experiment. You begin to treat it like a relic, rather than a companion.

That’s why I often say to my students: At the end of the day, a guqin is still a piece of wood. A special piece of wood, yes—but one you must press, pluck, and breathe with. If you fear it, you won’t touch it. If you worship it, you won’t hear it.

Choose something your hands can use without fear. Choose something your heart can accept without guilt.

If You Must Choose Alone

Even without a teacher, not all is lost. There are still careful steps you can take. Begin by identifying guqin that are personally made by contemporary makers with real standing. These are often described in clear terms: whose hands built it, what year, what materials. That is your only compass.

Ignore visual decoration. Ignore poetic names. Ignore prices that seem too good or too dramatic. Focus instead on clarity: who made this, and can their work be traced?

And once you’ve narrowed it down—don’t ask whether the guqin “feels right.” You aren’t ready for that. Instead, ask: Will this allow me to learn without being misled? That is the only correct question at the beginning.

Price: How Much Is Enough?

There is no fixed number, but there is a mindset. You don’t need to spend a fortune. But you do need to spend enough to honor your intention.

Think of it this way: you’re not buying an instrument, you’re entering a commitment. The price is not for sound alone—it is for time, for space, for silence made audible. If the amount feels like a token, it probably is. If it feels like a quiet stretch, you’re probably close.

In Closing

Choosing your first guqin is not a technical act. It’s an emotional decision wrapped in practical questions. Don’t rush it. Don’t romanticize it. Begin with something you can sit with, even when your fingers hurt. Begin with something you don’t need to explain to anyone.

Let it be a companion, not a symbol. Let it be a beginning, not a prize.

For a complete introduction to the guqin, including its history, playing style, and cultural roots, visit our full guide: What is Guqin? The Ultimate Guide →